The inflation surge over the past three years followed a unique disruption to the global economy.

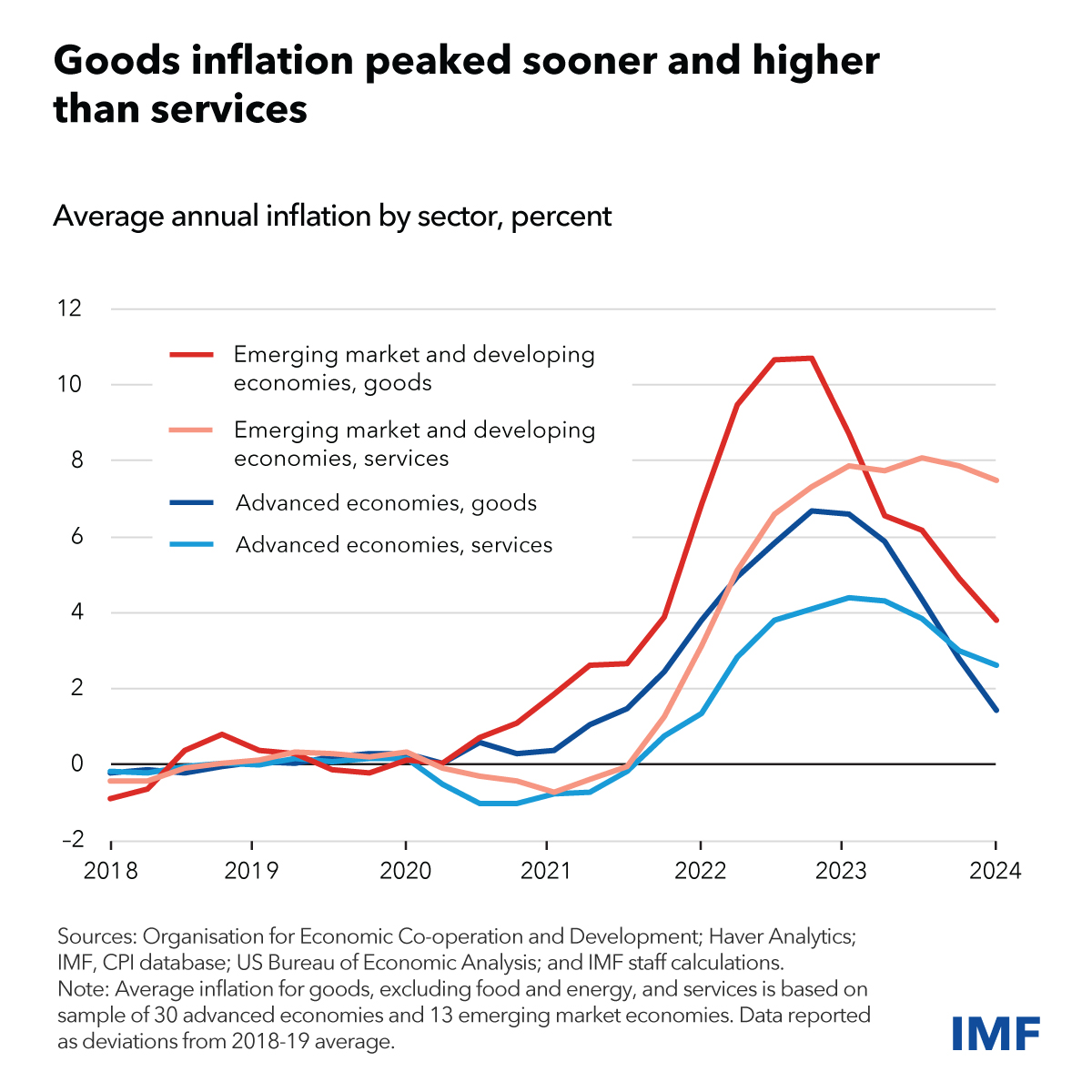

Pandemic lockdowns initially tilted demand away from services and toward goods. But this came at a time when unprecedented fiscal and monetary stimulus boosted demand, and many firms were not able to ramp up production fast enough, resulting in mismatches between supply and demand and rising prices in some sectors.

For example, ports were stretched to or beyond their capacity, partly due to pandemic-related staffing shortages, so as demand for goods surged, this resulted in backorders. When economies reopened, demand for services came roaring back and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine sent commodity prices soaring, in turn pushing global inflation to its highest level since the 1970s.

Our chapter of the latest World Economic Outlook reflects on this episode, drawing lessons—both new and old—for monetary policy.

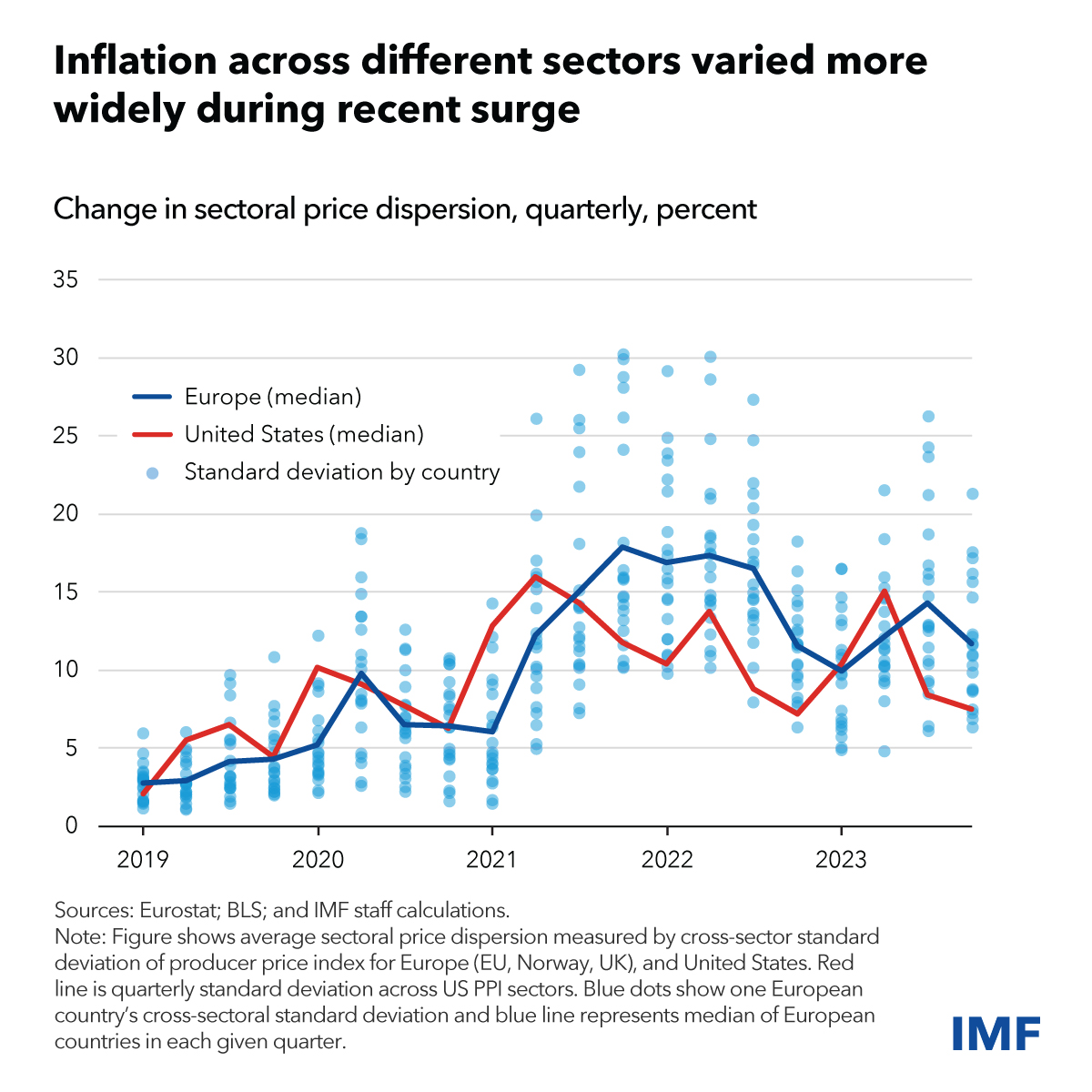

To understand the recent global inflation surge, we need to delve beyond traditional macroeconomic aggregates. Our modeling shows how inflation spikes in specific sectors became embedded in core inflation, a less volatile measure that excludes food and energy. Key to our analysis is the interaction between soaring demand and sector-specific bottlenecks and shocks. These caused large shifts in relative prices that resulted in an unusual dispersion of prices.

When supply bottlenecks became widespread and interacted with strong demand, the Phillips curve—the main gauge of the relationship between inflation and economic slack—steepened and shifted upwards. The steeper Phillips curve implied that relatively small changes in economic slack could have large effect on inflation. That came with bad news and good news.

The bad: inflation surged as many sectors hit capacity constraints. The good: it was possible to curb inflation at a lower cost in terms of lost economic output.

This last insight leads us to the new lesson: widespread supply bottlenecks can present central banks with a favorable tradeoff when confronting a demand surge. Because the Philips curve becomes steeper in such cases, policy tightening can be particularly effective at rapidly bringing down inflation with limited output costs.

However, when bottlenecks are confined to specific sectors with relatively flexible prices, such as commodities, we are reminded of an old lesson: the common practice of focusing monetary policy on core inflation measures remains appropriate. Excessive policy tightening in such cases can be counterproductive, leading to leading to costly economic contraction and resource misallocation.

Given these insights, central bank monetary policy frameworks should identify the conditions under which front-loaded tightening is appropriate. This requires enhanced models and better sectoral data to gauge underlying inflationary forces, improve forecasts, and guide the fine-tuning of policy responses. A first step in the right direction may involve collecting more frequent data for prices by sector and supply constraints to determine if key sectors are bumping against supply bottlenecks. Also, understanding structural factors such as how different sectors set prices and the links between them would provide additional valuable insights.

Several central banks plan to review their policy frameworks in the coming months. These reviews present an opportunity to incorporate well-defined escape clauses in their frameworks to tackle inflationary pressures when aggregate Phillips curves steepen. Forward guidance should internalize those escape clauses and allow for front-loading of tightening in such situations.

Such added flexibility should allow central banks to be better prepared in the future and help safeguard their hard-earned credibility.

—This blog is based on Chapter 2 of the October 2024 World Economic Outlook, “The Great Tightening: Insights from The Recent Inflation Episode.” This blog also reflects contributions by Emine Boz, Thomas Kroen, Galip Kemal Ozhan, Nicholas Sander, and Sihwan Yang.